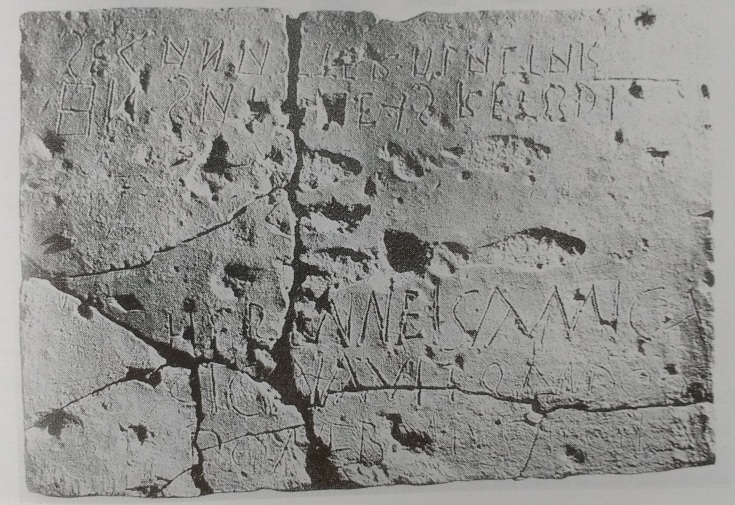

hn. sattiieis. detfri

segnatted. plavtad

herennis. amica

signauit. qando. a-

ponebamus. tegila(m)

Detfri of Hn. Sattis signed with a footprint.

Amica of Herens signed when we were laying out the tile.

Oscan/Latin inscription and four shoe prints on a large clay roof tile (0.67 x 0.94m). Pietrabbondante, c. 100 BC. Imagines Italicae: Teruentum 25; Sabellische Texte: Sa 35. Image from Imagines Italicae.

This inscription is an evocative glimpse into the lives of enslaved women in ancient Italy. In fact it’s two inscriptions, in two different hands, written into the wet clay of a newly-made roof tile to accompany two pairs of shoe prints. The tile was found at the large sanctuary site of Pietrabbondante (we don’t know its ancient name), and it’s possible that this tile was made during the re-roofing of a portico next to a large temple.

There are many surprises here. The most basic one is that two slave women (or possibly freedwomen) whose job involved shaping and laying out clay roof tiles to dry were able to read and write. And not just their names – each of them has written a full sentence. Who taught them to read and write? Did they use writing regularly, perhaps for simple record-keeping or for marking the tiles? Was the ability to read and write common for slaves at the sanctuary? In a society where (probably) less than 10% of women were literate, texts written by enslaved or low-status free women in their own hand are incredibly rare. In fact, I’m not sure I can think of another example off-hand.

Secondly, the doodled messages are written in two different languages. Detfri (if that is a name) has written in Oscan; Amica has written in Latin. This situation means without a doubt that at least one of the slaves was bilingual. The footprints and texts must have been written in the wet clay on the same day, before the tile dried out. To write such a similar message in two different languages, Detfri and Amica must have been able to speak to each other. Pietrabbondante is deep in the mountains of Samnium, an Oscan-speaking area, so it may be that Amica was a slave who was bilingual in Oscan and Latin. There are further clues that she was bilingual. Her owner’s name is Herens – an Oscan name, which she declines with an Oscan genitive ending even though she’s writing in Latin. She may have been deferring to his native language (writing his name the way he would write it himself), or mixing endings from the two languages she spoke, but either way it looks as though Amica could speak both Latin and Oscan.

And they’ve not just written in two different languages, but in two different scripts: Detfri’s sentence is in Oscan in the Central Oscan alphabet (transcribed in bold), while Amica’s Latin is in the Latin alphabet (transcribed in italics). So either they learned to write separately or – if one taught the other to write – at least one of them was bi-literate as well as bilingual. Neither makes any unusual spelling mistakes that would suggest lack of familiarity with the language or script. Things like qando for quando are fairly normal, although non-standard, spellings. Amica leaves the final -m off teglia(m), and that’s very common in Latin inscriptions too. It’s possible that even by 100 BC not all speakers pronounced the final -m, or pronounced it only as a nasalisation of the preceding vowel. So there are spelling ‘errors’ in a sense, but they are native-speaker errors.

Thirdly, the name or word detfri is a mystery. If it is a name, it’s not one that we know from anywhere else. If it’s a job or title, we can’t make sense of it either. Perhaps it was an Oscan name, or a name from whatever part of the world the woman came from originally (because, of course, most of the slaves in Italy in the first century BC were trafficked there from elsewhere). Amica is a common name given to slaves in Latin – it just means “friend”. I tend to think that Detfri is a name, though not one we can make sense of, with the two inscriptions paralleling each other very closely.

I can’t help imagining the day when this inscription was written. Two slaves, working in conditions that were no doubt very difficult, taking a little time to mess about as friends and enjoy each other’s company. But where did they come from? What led them to this point? And what happened next? Did they get in trouble? Was the tile already useless enough that it didn’t matter? Just a few years later, Pietrabbondante was destroyed by the Roman dictator Sulla during the Social War – were Detfri and Amica still there during that turbulent time? We have, perhaps, ten minutes of one day of these women’s lives documented – and that’s it. That’s all we have for so many ancient people, but somehow the casual, fun, almost temporary character of this inscription makes that very clear.

Thanks very much to Dan Diffendale for his images of Pietrabbondante, which make me want to go and live there. You can see more of his photos here.

Leave a comment